Will there ever be another Bibliotheca Alexandrina?

Edward Vanhoutte

edward.vanhoutte@kantl.beFor centuries, mankind has been using written records for mainly three reasons: communication, documentation, and distribution of information. Written records of any kind have been materialized in such incidental forms as stylus tablets, scrolls, and books. The advent of the electronic paradigm and the development of hypertext-technology has changed this model drastically. Authors of both creative and business texts have entered the electronic world by making use of wordprocessors and text-editors. By adding a flair of hypertext to their documents for purpose of display and distribution over the Internet and the WWW, they become their own publishers. In order not to become obsolete, both business partners such as commercial publishers, royalty offices and distribution centres, and partners from the academic and the public world - libraries and universities - must look to revitalize themselves in the new paradigm of first and second generation digital resources. Questions on accessibility, longevity and intellectual integrity become extremely saliant matters of concern to which international standards for the use of markup can provide an answer. Of course that's not the business plan of many booming dotcom-companies which try to force their own proprietary formats on to the textual world.

1. The Materialization of Text

Texts form the very core of our world and our society. Everything is language, and nothing sensible can be said about moments in time of which we have no written records. That's why we have to take care of the preservation of previously written records and the way in which we create new written records. Especally in the digital paradigm.

Written records of any kind are the result of the urge man had/has to materialize communication. Conmmunication, then, is the system which is oriented towards the conveyance of meanings, by making use of some sort of code, which we call language. The linguist Jakobson explains this system by his famous communicative classification model (Jakobson, 1960). Language, according to Jakobson, is a code which can represent a message about some referential matter in the outside world. One subject can distribute that message amongst other subjects by making use of some kind of medium. The six moments in a communicative process are thus: referent, message, sender, receiver, medium (channel), and code.

The two problematic actors in the transportation of this model through history are the entwinded concepts and realizations of the human subject and the medium. From a certain moment in time, mankind has tried to preserve texts by committing them to physical surfaces such as rock, birch bark, stone, wax tablets, papyrus, vellum, parchment, and paper. This quick overview of the material history of written records is certainly not complete, but it provides us with a good sample on which we can elaborate. Each and every writing surface comes with its limitations and possibilities, which explain why the writing process of a book scroll is essentailly different from engraving a stone or writing on parchment which form gatherings intended to create a codex. Scholarly disciplines such as analytical bibliography and history of the book, study this area of interest, and have shown that man had to adopt his writing techniques to the coincidental form of the writing surface. At the same time, the scribe of any sort of text or document was looking - in his own historical context - for the best form in which to do so. The constant concern to render a user friendly and correct image of the message resulted in the addition of lay-out to the text. Majuscules, miniscules, spacing, punctuation, ruling, rubrication, divisions of any sort, titles, running titles, italics, lists, page numbers, etc... came in use gradually in order to represent the logical structure of the text. The reader of such texts could easily decode this encoding of the logical structure of the text in the reading process. General lay-out conventions for the display of texts came in use and served to the reader as a key for his code-cracking. The result of this evolution is for example that no one will argue about the title of this chapter or this very article, because everyone happens to know that the title of a text can be found in bold at the top of that text. The same is true when reading a word in italics. The use of italics can e.g. signal the emphatic use of a word. In order to make clear to the scribe, composer, typist or printer how the written, typed or printed text should be rendered, markup was invented. Markup is in fact nothing else but additional procedural information about the lay-out of the text. In the Middle Ages this markup told the rubricator for instance which words to put in red, where to insert an illumination, etc. With the automation of the text industry, the term markup was being used for all specific lay-out instructions: the annotations of copy editors "with instructions to the typesetter concerning layout, fonts, spacing, indentation, and so on" (van Herwijnen, 1995: 17). The computer driven printing industry soon came to adopt the same term for the system which documents typesetting procedures alongside the actual data or, in the case of wordprocessors, in the same format of the data.

A machine sees a text as a consecutive string of characters which is stored in a proprietary format according to the wordprocessor or typesetting programme used. Markup (all additional information added to a text) articulates to the computer what the human reader reads implicitly. That's why markup is essential for the creation of a machine-readable text. Each wordprocessor or text-editor uses its own proprietary markup system which can only be fully understood by that very programme. This markup or encoding is procedural: it documents the appearance or display of a text on paper or on the screen. It prescribes the lay-out of the text. What the text says and how I want that to be displayed (markup) is being stored in the same proprietary format, which explains why the interchange between software and platforms is problematic. The software companies are very aware of this problem and add several conversion modules to their programmes, but 100% compatibility is still a utopistic goal.

The problem of the proprietary reduction of semantics to the encoding of lay-out becomes prominent when we want to integrate the computer and machine readable texts in scholarly research. The problems are threefold: scholarly research is oriented towards accessibility, longevity, and intellectual integrity, none of which can be guaranteed by whatever proprietary software package. Humanities Computing needs encoding standards which enable the interchange between platforms and software, which guarantee a maximal lifetime of the electronic text, and which provides the scholarly community with tools, not to express what a text should look like, but what a text means. Academia needs generic and descriptive instead of procedural and prescriptive encoding. As an illustration, let's go back to the example of the use of italics I gave before. In a text, the use of italics can signal the emphatic meaning of a word, but italics are also used to flag a foreign word in a text, or to distinguish e.g. the title of a book or a movie from the rest of the text. A wordprocessor will use the same procedural markup for all three of these instances, which is very unpractical for the purpose of research. How will a scholar be able to retrieve all french words in a corpus of say 100 texts? By instructing the wordprocessor to look for all instances of the use of italics? In that case the hits will also contain every emphasized word in the texts or all mentions of book or movie titles. It would be much more useful to have a markup system which can express what a certain string of characters is, e.g. book title or french word. This way, the scholar will be able to develop very precise search strategies, and the computer will be able to compute semantics as well.

To summarize, the humanities computing scholar is looking for a non-proprietary and generally accepted markup standard which:

- separates the logical elements of a document,

- separates form and content, and

- specifies the processing instructions to be performed on those elements.

2. Markup Languages

In the mid seventies, a couple of generic markup languages were developed on the basis of earlier formatting languages: GML (Generalized Markup Language) was based on IBM Script, Syspub on Waterloo Script, and ms on nroff/troff. Later, LaTeX was written for TEX. They functioned as stylesheets avant la lettre in that they group formatting instructions which can be applied to a text or a group of texts.

SGML (Generalized Markup Language) goes beyond generic markup by formalizing the document representation and enabling text interchange. A markup language must specify what markup is allowed, what markup is required, how markup is to be distinguished from text, and what markup means. (Sperberg-McQueen & Burnard, 1994: 13). SGML provides the means for doing the first three, documentation to a specific application of SGML is required for the last. Therefore, SGML is not itself a markup language but provides the elements to build an unlimited variety of generic markup languages, the most popular of which is HTML. In 1986 SGML was published as the ISO 8879 standard for document representation. In the specifications own wording:

'This international Standard specifies a language for document representation referred to as the "Standard Generalized Markup Language" (SGML). SGML can be used for publishing in its broadest definition, ranging from single medium conventional publishing to multi-media data base publishing. SGML can also be used in office document processing when the benefits of human readability and interchange with publishing systems are required.' (Goldfarb, 1990: 238)

SGML is built on three principles (cf. Vanhoutte, 1998: 113-120):

- SGML describes the structure of texts,

- SGML prescribes the structure of texts, and

- SGML guarantees data independence.

SGML does all that by taking plain ASCII files as a basis for generic enrichment of texts. An SGML application can, for instance, delimit all instances of names with the <NAME> </NAME> pair, or mark the beginning and end of a text with the tags <TEXT> </TEXT>, etc. A stylesheet language can then be applied to the document to render all names e.g. in italics, and all texts in Garamond 12pt. As a result, SGML enables content to be exchanged and processed in a controlled manner irrespective of its tangible form or lay-out. Soon, SGML became the preferred interchange format for document structure and encoding in the worlds of industry, busines, and defense, where data management and flexible publication methods form the very core of their existence.

'Data is a computer's raw material. Knowing the structure and meaning of the data, and knowing the output you want to produce, can exploit the speed and accuracy of the computer to produce the output. [...] While today's WYSIWYG writing tools produce predictably formatted printed pages, the files they create to store them are highly unpredictable.' (Ensign, 1997: 19)

The academic world too is very much involved in data management and the quest for flexible publication solutions. Together with this, transportability in time, and over platforms and software is in high demand in scholarly work. The advent and growth of the WWW and the work of the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) has proved the case of the power of SGML applications to the academic community. It is characteristic of the enthusiasm by which the scholarly communtity has embraced and developed the markup technology that the design and the features of the new business standard XML owes so much to Humanities Computing.

Hence the wide array of users from both worlds who have succesfully used SGML over the last 25 years: novelists, technical writers, computational linguists, librarians, biblical scholars, dictionary makers, parliamentarians, paper publishers, electronic publishers, Braillists, musicians, builders of hypertexts, of expert systems, of airplanes and helicopters, of automatic translation software, etc.

3. SGML and Humanities Computing

Shortly after the official publication of ISO 8879, a diverse group of scholars from text archives, scholarly societies, and research projects gathered in November 1987 for a meeting on the problem of the proliferation of systems for representing textual material on computers.

'These systems were almost always incompatible, often poorly designed, and growing in number at nearly the same rapid rate as the electronic text projects themselves. This threatened to block the development of the full potential of computers to support humanistic inquiry - by inhibiting the sharing of data and theories, by making the development of common tools arduous and inefficient, and by slowing the development of a body of best practice in encoding system design' (Mylonas & Renear, 1999: 3)

As a result of the debate and work which had been initiated by that meeting, the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) was born as a growing group of scholars who wanted to establish a standard for electronic text encoding and interchange. Very early in their proceedings, the choice was made for SGML as the meta-language for a specification, and the TEI markup language was articulated as a set of SGML DTD's (Document Type Definition). The first official publication of the Guidelines was published in 1994 and corrected in 1999. These P3 Guidelines, a 2 volume, 1300 pages documentation, (Sperberg-McQueen & Burnard, 1994), specify what the SGML markup in the TEI application means, and propose a set of DTD's for the encoding of virtually any kind of text for scholarly research. As Michael Sperberg-McQueen has pointed out,

'The TEI guidelines do not represent the first concerted attempt since the invention of computers to develop a general-purpose scheme for representing texts in electronic form for purposes or research-but they do represent the furst such attempt(Sperberg-McQueen, 1996: 49)

- which was not limited to a single institution, but attempted instead to register the consensus of the entire community of interested researchers;

- which attempted to cover all types of text, in all languages and scripts, from all periods;

- which attempted to support all types of research rather than being limited to specific disciplines; and

- which actually came to fruition instead of perishing somewhere along the way.'

TEI has become the widely accepted standard for text encoding and interchange in the Humanities, and in the decade of its existence, dozens of academic projects have adopted the guidelines in their work (for an overview of these projects, see the TEI Application page).

As pointed out before, the work of the TEI and especially the TEI Xpointer and Xlink syntax (DeRose & Durand, 1995) which realizes the concept of hypertext in TEI, have been instrumental in the creation of XML (eXtensible Markup Language) (DeRose, 1999). Whereas the SGML specification is a voluminous book (Goldfarb, 1990), the XML 1.0 spec only counts thirty odd pages (hence it is beyond my understanding why publishers keep on publishing 350 page books on XML), and promises the power of SGML with the ease of HTML. HTML is an application of SGML, while XML is specified as a profile (or subset) of SGML. The XMLization of TEI will no doubt be the next widely accepted standard for research in the Humanities.

4. Electronic Texts, Archives and Libraries

The famous library of Alexandria has presumably been founded by Ptolemaeus I and his heirs in the fourth century before the common era. In its highdays, the library is believed to have held approximately half a million bookscrolls from all over the world. Each ship which cast anchor in the floroushing harbour of Alexandria was obliged to supply a manuscript or a bookscroll to the library for copying. The original was being kept by the library and the copy went back to the suppliers. This way, the Bibliotheca Alexandrina managed to build a collection of mythical proportions which mirorred the text production of the ancient world. A clever classification scheme must have enabled the interested scholar to consult the scrolls, and once the language barrier was taken - many texts were being translated into Greek, the Lingua Franca of that moment - he could read his way through all the knowledge of the world. The Alexandrian library could have become the largest and the most excessive archive of human history, but destiny decided otherwise. Together with the library, which burned down during the last half of the first century b.c.e., most of the literature and knowledge of the ancient world disappeared. There are still many theories as to the conditions in which this disaster happened, but one thing is sure: book scrolls burn well. Although the physical form of a text is but a coincidence, the text may disappear forever with the disintegration of that form, which happened with hundreds of creative works of Greek authors from the first 500 years of Hellenism.

The preservation and conservation of any physical unit (of text) has always been a prominent purpose of a library or an archival institution. At the same time, the texts kept in the physical forms must be held accessible for interested readers. Over the course of time, and especially with the advent of new technology and multimedia, all kinds of solutions have been suggested, of which digitization is the most recent one. 'Digitization is quite simply the creation of a computerised representation of a printed analog.' (Morrison, Popham & Wikander, 2000). This can be realized through imaging, OCR'ing, and re-keying, or through a combination of all this. If we don't want an Alexandrian disaster to happen, we have to make sure we store the digitized documents in a reliable and open format. SGML-TEI is the preferred choice for this, because it does not only provide the creator of the document with the possibility of deciding on the granularity of information he wants to encode, it is also a standardized and non-proprietary interchange format between systems and platforms, it is completely software independent, and it produces human- as well as machine-readable documents. The use of and need for standards and protocols is being demonstrated by the structure of the WWW which is often called a big library.

That's why text archives, digital libraries, and creators of first and second generation digital resources (better) rely on applications of SGML or XML. We may not create information and data for eternity, but we certainly don't want that data to be inaccessible within 5 years time (the average lifetime of software).

5. The Electronic-critical Edition of De teleurgang van den Waterhoek

Bringing a text to the public is not the solitary activity of the author, but a co-ordinated sociological process in which the author, the publisher, the typesetter, and many other people or instances play a decisive role. It is therefore naieve to consider a book on the shelf in the bookstore as being identical to the text the author wrote. All sorts of things can go wrong: typo's, errors, emendation, censorship, modernizing, adaptation, etc. can result in a different text. From the fourth century c.e. onwards, scholars in the Bibliohteca Alexandrina and all over the world have studied texts to constitute an authentic and reliable version, which can e.g. be used as the basis for literary criticism. Textual criticism, which is the scholarly discipline which tries to constitute reliable texts, has become a fundamental science with its own journals, training, publications, and schools. The history of a text and the genetic process of writing and publishing tells a lot about texts.

In the case of Stijn Streuvels' De teleurgang van den Waterhoek for example, the second print edition from 1939 differs extensively from the first print edition from 1927. The drastically revised edition of 1939 only retained 73.4% of the original text of the first print edition and was probably the author's response to both the publisher's request to produce a shorter and hence a more marketable book, and the catholic critique who had fulminated against the elaborate depiction of the erotic relationship between two of the main characters: the headstrong and voluptuous village girl Mira and Maurice, the reserved but promising engineer from the city. Mainly for commercial reasons, Streuvels made his novel less offensive for catholic Flanders and literally crossed out the denounced passages on his copy of the first print edition which then served as a printer's manuscript for the second print edition. This "filtered" version of the text especially lacks the essential psychological descriptions which give depth to the main characters. Up to 1987, this revised text had been the basis for 13 reprints of the book, and for most of literary criticism, thus presenting a deformed text and image of the text to generations of interested readers and students of literature.

On the basis of archival material and all of the extant authorial versions of the novel, Marcel De Smedt, a professor in textual criticism at the K.U.Leuven, and I have tried to restore the original version of the novel, and contextualize it by situating it in its genetic history. The Streuvels papers, which can all be found in the Archive and Museum for Flemish Cultural Life in Antwerp (AMVC, Archief en Museum voor het Vlaamse Cultuurleven), and which formed the basis of our research contain:

- a defective draft manuscript from 1926 (S935/H15)

- a complete neat manuscript from 1927 (S935/H18)

- a corrected typescript (1927) (S935/H16)

- a corrected and annotated copy of the prepublication of the novel in the literary journal De Gids which functioned as manuscript for the first print edition of 1927 (S935/H17)

- a defective corrected proof (S935/H17)

- an elaborately edited version of the first print which functioned as manuscript for the second revised edition of 1939 (S935/H24)

- a small set of paralipomena

In 1998, the Royal Academy of Dutch Language and Literature (Koninklijke Academie voor Nederlandse Taal- en Letterkunde, Gent) created the Electronic Streuvels Project (ESP) which had as it main goal the electronic-critical edition of Stijn Streuvels' De teleurgang van den Waterhoek. So far, both a text-critical reading edition in bookform (De Smedt & Vanhoutte, 1999), and an electronic-critical edition on CD-Rom (De Smedt & Vanhoutte, 2000) have been published as spin-off products from the ESP.

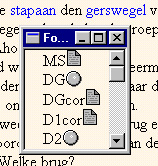

From the beginning of the project, the ESP opted for the SGML (ISO 8879) approach to text encoding and markup. For the markup of six documentary sources included in the electronic edition, the ESP made use of the TEI Lite DTD, a fully compatible subset of the complete TEI scheme. They are, with their corresponding sigla:

- MS: complete neat manuscript (1927).

- DG: prepublication in the literary journal De Gids (1927).

- DGcor: version of De Gids corrected by Streuvels (1927).

- D1: first print edition (1927).

- D1cor: version of the first print edition corrected by Streuvels [1939].

- D2: second revised print edition (1939).

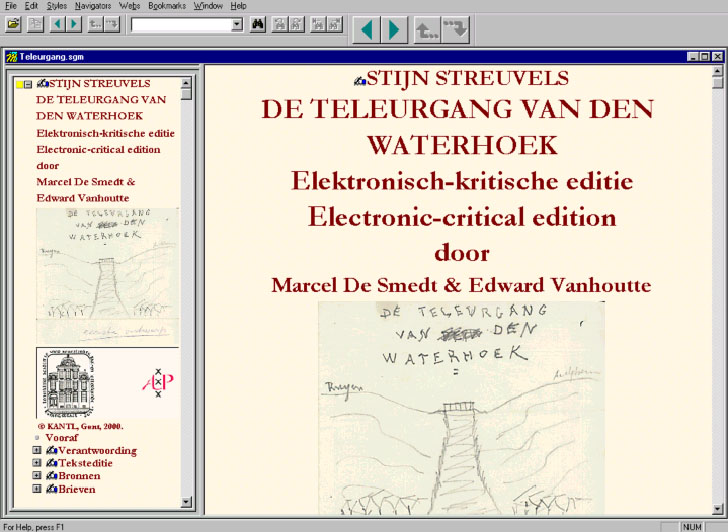

On launching the electronic edition from the CD-Rom, the user gets the opening screen (Figure 1). We are using the programme MultiDoc Pro CD Browser, an on-the-fly SGML browser from Citec, to present our work. To the left you can see the dynamic-interactive table of contents, and the text is displayed in the document window to the right. As one can see from the table of contents, the edition consists of four major parts, preceded by a Vooraf (Preface). The parts are:

- Verantwoording (Account of underlying principles): consisting of the chapters "Ontstaansgeschiedenis" (genetic history), "Basistekst en tekstconstitutie" (base text and text constitution) and "Overlevering" (transmission history).

- Teksteditie (Hypertext Edition): presents all the paragraph variants from the 6 documentary sources included in the edition against the orientation text by making use of hypertextual features.

- Bronnen (Documentary Sources): includes the full-text versions of DG, D1 and D2, and the facsimile-editions of MS, DGcor, and D1cor.

- Brieven (Letters): presents the diplomatic edition of the correspondence between the author and his publishers and friends; Geerardijn-Streuvels, Veen-Streuvels, Colenbrander-Streuvels, Streuvels-Eeckhout and Eeckhout-Streuvels.

Clicking on an item in this table of contents displays the corresponding section in the document window, clicking on a plus-sign reveals underlying sections, a yellow square keeps track of where the user is in the edition and prevents him from getting lost, and a small hand-icon marks the places where handy snippets of users' instructions can be found. Apart from the table of contents, there are four more tools to navigate one's way through the edition: the scrollbar to the right-hand side of a window, the "Previous page" and "Next page" buttons in the taskbar at the top, user defined Web-files, and command-line arguments and DDE commands.

The section Verantwoording consists of three subsections:

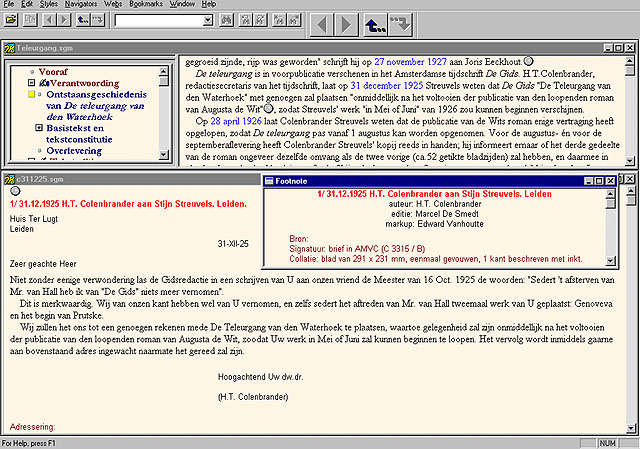

- the first of which ('Ontstaansgeschiedenis van De teleurgang van den Waterhoek') is a scholarly article on the genesis of the novel. This article cites from and refers extensively to the correspondence between Stijn Streuvels and his publishers and friends. By providing hyperlinks to the diplomatic edition of the corresponding letters, the reader of the article can immediately check and read the relevant passages (figure 2) which launch in separate windows. Conventional notes are provided with the article as well as links to digital facsimiles of relevant material from the Streuvels archive.

- In a second subsection ('Basistekst en tekstconstitutie') the editorial principles for the constitution of the full text versions are articulated. The treatment of spelling, punctuation, and emendations are clarified for each of the full text sources, and a list of corrections is provided for the critical texts. The edition presents two critical texts (D1 & D2), one of which (D1) is used as the orientation text in the hypertext edition. The text of the prepublication (DG) has not been emended, though corruptions are encoded using the <SIC> element (76 in total) and corrections are suggested in a CORR attribute. A different approach was chosen for the critical texts, where emendations are encoded using the <CORR> element and the original reading is put inside a <SIC> attribute. Whereas D2 only retains 73.4% of the text of D1, more emendations had to be made (93 and 73 respectively). Further, the editor responsible for each of the corrections is documented inside a RESP attribute to the <CORR> tag, allowing the user a maximum control over the editorial work. The choice for two critical texts is a sociological one. Since both the first print edition and the second print edition have been received by the public and literary criticism, it would be unwise to neglect the cultural validation and the position of both these texts in the history of Flemish literature. The first print edition does present e.g. a more complete psychological depiction of the main characters and has therefore been contested, but the revised version of the second print edition is the text that generations of readers have read and studied.

- The third subsection ('Overlevering') lists the transmission history of the text and provides a description of all extant complex and linear documentary sources (manuscripts, typescripts, corrected proofs and prints, and subsequent print editions). This section also provides an entry to the third major part of the CD-Rom ('Bronnen'), by linking the description of a documentary source included in the edition to the location where that source can be consulted.

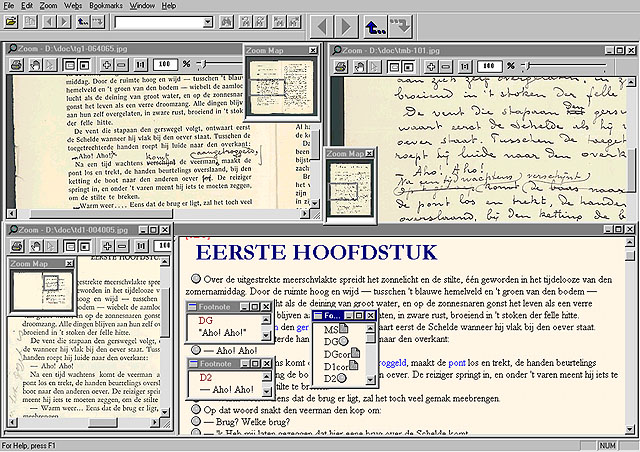

Indeed, not only full text versions of DG, D1, and D2 are included in the edition, the user can also consult the facsimile editions of MS, DGcor, and D1cor. The third part of the edition presents the six versions of the text chronologically, which allows the user to consult each of them separately. It is of course true that 'every form of reproduction can lie, by providing a range of possibilities for interpretation that is different from the one offered by the original' (Tanselle, 1989: 33) and the process of imaging is a process of interpretation. In order for the user of the edition to be able to evaluate what he sees, the facsimile editions are accompanied by a full account of the imaging procedure including the documentation on the soft- and hardware (and settings) used in the project, which I believe is an essential requirement. No facsimile can of course substitute the original, but it is the best approximation we can offer the interested user.

But the essential part of the edition is to be found in the section 'Teksteditie'. This part of the electronic-critical edition presents the constituted text of D1 as the orientation text around which the hypertext presentation of textual variation is organized. Instead of linking the orientation text to an apparatus variorum, the ESP opted for what I want to call a linkemic approach to textual variation. I define a linkeme as the smallest unit of linking in a given paradigm. This unit can be structural (word, verse, sentence, stanza, etc.) or semantic. In the case of the glossary provided with the orientation text, the linkeme is of a semantic class which can be defined as "the unit of language that needs explanation". In the case of the presentation of textual variation, the linkeme is a structural unit, namely the paragraph. In the actual hypertext edition it is possible to display all the variants of each paragraph in all six of the versions on the screen. This is made possible by a complicated architecture on the code side which allows for hypertext visualisation on the browser side. The linkemic approach to textual variation is realized as follows in the edition. Each paragraph of the orientation text is preceded by a grey round button. On clicking that button, a pop-up window containing five sigla is launched.  In this pop-up window, a grey round button behind a sigle points to a corresponding variant paragraph in full text, and a document icon points to a corresponding digital facsimile on which the variant paragraph of that version can be found. Because of the extension of the variant it is sometimes possible to find several links per sigle. Each variant full text paragraph is displayed in a pop-up window, which marks the sigle of the document source in red at the top of the window. Clicking a document icon behind a sigle launches a Zoom Window containing a digital facsimile of the page on which the corresponding paragraph in the respective complex documentary source is located. A project-specific hierarchic naming scheme allows the user to know exactly which facsimile is being displayed. This is explained and illustrated in the Manual provided on the CD-Rom. This linkemic approach provides the user with enough contextual information to study the genetic history of the text, and introduces new ways of reading the edition. Because of the fact that a new document window, displaying a version of the user's choice, can be opened alongside the hypertext edition, every user can decide on which text to read as his own base text. The hypertext edition can then be used as a sort of apparatus with any of the versions included in the edition. This way, hypertext and the linkemic approach enable the reading and study of multiple texts and corroborate the case for textual qualifications such as variation, instability and genetic (ontologic/teleologic) dynamism.

In this pop-up window, a grey round button behind a sigle points to a corresponding variant paragraph in full text, and a document icon points to a corresponding digital facsimile on which the variant paragraph of that version can be found. Because of the extension of the variant it is sometimes possible to find several links per sigle. Each variant full text paragraph is displayed in a pop-up window, which marks the sigle of the document source in red at the top of the window. Clicking a document icon behind a sigle launches a Zoom Window containing a digital facsimile of the page on which the corresponding paragraph in the respective complex documentary source is located. A project-specific hierarchic naming scheme allows the user to know exactly which facsimile is being displayed. This is explained and illustrated in the Manual provided on the CD-Rom. This linkemic approach provides the user with enough contextual information to study the genetic history of the text, and introduces new ways of reading the edition. Because of the fact that a new document window, displaying a version of the user's choice, can be opened alongside the hypertext edition, every user can decide on which text to read as his own base text. The hypertext edition can then be used as a sort of apparatus with any of the versions included in the edition. This way, hypertext and the linkemic approach enable the reading and study of multiple texts and corroborate the case for textual qualifications such as variation, instability and genetic (ontologic/teleologic) dynamism.

The fourth and last major part of the edition presents the diplomatic edition of 71 letters from the correspondence between Stijn Streuvels and his publishers and friends. The letters all deal with the genesis of the novel, and are ordered chronologically per correspondent in a hypertextual list. The letters are encoded in conformation with the project-specific StreuLet DTD and can be displayed on the screen by clicking on the hyperlink. The editorial principles of this diplomatic edition are outlined in the subsection 'Verantwoording' to this part. For each letter the following information is documented:

- the catalogue number in the diplomatic edition, the uniform date notation, the sender's and recipient's name, the mailing location,

- the name of the author of the letter,

- the name of the editor of the letter,

- the name of the researcher responsible for the markup,

- the document description, i.e. archive signature and collation (description of writing material, format in mm, paper colour, number of written pages, note on whether the letter is typewritten or written by hand).

So far, the electronic-critical edition has been presented as a stable, closed, and "fixed" package which demonstrates textual instability and multiplicity through a webbing of cross-references which the user is free to discover at his own pace and according to his own goals. But true hypertext is inherently unstable. True hypertext should not only invite readers to maximally participate in the process of establishing the edition through the possibility to create their own reading paths. True hypertext should also enable users to add to it:

'Annotation tools (again, possibly the same tools used by authors) allow readers to create and publish responses to published writings, adding their own insights and perspectives to the range of possible texts other readers may encounter. Readers can also add their own links between extant works, making connections that the original authors did not, or creating entirely new links based on completely different principles. (They cannot modify already-published writing, however.) This ability for new readers to contribute to hypertexts, combined the ability of authors to modify originals, makes it impossible to speak of hypertexts as "finished:" rather, they are inherently unstable.' (Pang, 1994)

In the electronic-critical edition, every user can enrich the edition with his own annotations, bookmarks and hyperlinks by making use of the Personal Webs feature. User defined links for retrieval of locations in a document (Bookmarks) can be inserted anywhere in the edition. The user can annotate each string of text (Figure 5) or spot on a digital facsimile, and create user defined bidirectional hyperlinks between text and/or facsimiles. It is of course true that the user cannot alter the editor's constructions and text, but this facility breaks the edition open and enables the establishment of critical thinking and the application of personal insights on the edition. Personal Web files are SGML files that use the HyTime addressing concepts (ISO 10744:1992) and they are stored on the user's hard drive. The concept of storing annotations, bookmarks, and hyperlinks in a separate web file instead of encoding them in the main document, opens a number of interesting possibilities for new kinds of research and teaching. It allows the user to:

- Superimpose alternative hypertext structures onto a single document.

- Attach all sorts of information to a document without changing the document itself.

- Distribute only a set of personal comments to the edition to fellow users, given they own a personal copy of the edition.

- Receive comments of several users of the edition and display them on the screen simultaneously (with each user using a personal set of icons for their comments).

6. Towards new Publishing Combinations

Together with the electronic edition on CD-Rom, a reading edition in bookform was published. The text for the reading edition was directly generated from the TEI files, and only had to be formatted for print. But the most important revolution in the relationship with the publisher came with the electronic publication. Whereas the author or scholar traditionally supplies content which needs editing by the desk editor, lay-outing, typesetting, printing, producing, distributing, and marketing, the publisher Amsterdam University Press only had to produce, distribute, and market the electronic edition. The master CD was created without interference from the publisher, and AUP only had to multiply it and make sure the world knew about the product. Electronic publishing forces traditional publishing houses in a different role and asks for new publishing combinations, especially with respect to scholarly products.

Markup has moved from the printing press to the author, which makes it all the more important to do it right at once.

Edward Vanhoutte (edward.vanhoutte@kantl.be) is co-ordinator of the Centre for Textual Criticism and Document Studies in Ghent (Centrum voor Teksteditie en Bronnenstudie - CTB) and SGML/XML consultant in different academic projects in Belgium and The Netherlands. He publishes widely on textual and genetic criticism and electronic scholarly editing, and runs graduate courses on textual criticism and electronic publishing at the University of Antwerp (UIA). Amongst his most recent publications are the text-critical reading edition in bookform (Manteau, 1999) and the electronic-critical edition on CD-Rom of Stijn Streuvels' De teleurgang van den Waterhoek (Amsterdam University Press/KANTL, 2000) which he prepared together with Marcel De Smedt.

Useful links

- Amsterdam University Press: http://www.aup.nl

- AMVC, Archief en Museum voor het Vlaamse Cultuurleven: http://www.dma.be/cultuur/amvc

- Creating and Documenting Electronic Texts: A Guide to Good Practice: http://ota.ahds.ac.uk/documents/creating/

- First Monday: http://www.firstmonday.dk/

- The TEI Consortium: http://ww.tei-c.org

- The XML Cover pages: http://www.oasis-open.org/cover/sgml-xml.html

- The W3C: http://www.w3c.org

References

- DeRose, Steven J. & David G. Durand (1995). 'The TEI Hypertext Guidelines.' Computers and the Humanities 29. 181-190.

- DeRose, Steven (1999). 'XML an the TEI.' Computers and the Humanities 33. 11-30.

- De Smedt Marcel & Edward Vanhoutte (1999). Stijn Streuvels. De teleurgang van den Waterhoek. Tekstkritische editie. Antwerpen: Manteau.

- De Smedt Marcel & Edward Vanhoutte (2000). Stijn Streuvels. De teleurgang van den Waterhoek. Elektronisch-kritische editie/electronic-critical edition. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press/KANTL.

- Ensign, Chet (1997). SGML: The Billion Dollar Secret. New Jersey: Prentice Hall PTR.

- Goldfarb, Charles, F. (1990). The SGML Handbook. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 19955.

- Jakobson, R. (1960). 'Linguistics and poetics.' T. Sebeok. (ed.) Style in language. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. 350-379.

- Morrison, Alan, Michael Popham & Karen Wikander (2000). Creating and Documenting Electronic Texts: A Guide to Good Practice. Oxford: OTA. http://ota.ahds.ac.uk/documents/creating/

- Mylonas, Elli & Allen Renear (1999). 'The Text Encoding Initiative at 10: Not Just and Interchange Format Anymore - But a New Research Community.' Computers and the Humanities 33. 1-9.

- Pang, Alex Soojung-Kim (1997). 'Hypertext, the Next Generation: A Review and Research Agenda.' First Monday 3/11 (november 1997). http://www.firstmonday.dk/issues/issue3_11/pang/index.html

- Sperberg-McQueen, C. M. & Lou Burnard (eds.) (1994). Guidelines for Electronic Text Encoding and Interchange. (TEI P3). Chicago and Oxford: Text Encoding Initiative. Revised reprint (1999) available from http://www.tei-c.org/uic/ftp/P4beta/index.htm & http://www.hcu.oc.ac.uk/TEI/Guidelines/

- Sperberg-McQueen, C. M. (1996). 'Textual Criticism and the Text Encoding Initiative.' Richard J. Finneran (ed.), The Literary Text in the Digital Age. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. 37-61

- Tanselle, G. Thomas (1989). 'Reproductions and Scholarship.' Studies in Bibliography 42. 25-54.

- Van Herwijnen, Eric (1995). Practical SGML. Second edition. Boston/Dordrecht/London: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Vanhoutte, Edward (1998). '... en doende, denkt dan nog. SGML, TEI en editiewetenschap.' Edward Vanhoutte & Dirk Van Hulle (red.), Editiewetenschap <!--in de praktijk-->. Antwerpen: Genese. 107-133.

- Vanhoutte, Edward (2000). 'Het kaft als Boek. Over de grenzen van het boek.' DVG - De Vlaamse Gids, 84/2 (maart/april 2000). 10-13.

XHTML auteur: Edward Vanhoutte

Last revision: 26/03/2001